Abstract: This article describes the rediscovery of a small but historically-interesting collection of butterflies assembled by members of the Bree family, from Allesley in Warwickshire. Both the Rev. William Thomas Bree and his son, the Rev. William Bree, are cited in numerous 19th century books as being knowledgeable observers of butterflies.

In 2004 a butterfly collection was discovered in a lock-up garage in Coventry. Stored in a number of glazed boxes, it comprised a mixture of 19th and early-20th century specimens, but the only evidence of who had collected them came from a few labels mentioning the surname Bree. The owner subsequently contacted the Keeper of Natural History at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum in Coventry, with whom, by some good fortune, this author had corresponded six months before, to ask whether there were any insects collected by the Bree family hidden in the museum's collections. As a result, the two parties were put in contact with each other and the author was able to purchase the boxes.

That the collection had survived undamaged by pests, with so little care and attention, is impressive enough, but equally amazing is the fact that it was almost complete - being laid out in five out of what had most probably been a set of six storage boxes. So often, old collections like this one have been broken up and absorbed into the cabinets of others.

This particular collection appears to have been assembled by three members of the Bree family, being handed down from one to the other, between about 1830 and 1920. It therefore spans an era when new species were still being added to the list of our native fauna, whilst others were being lost from it. It is not a large collection (some 686 specimens remain) and does not contain many obvious aberrations. However, what makes the collection of particular interest is that both the boxes in which the butterflies are stored, and some of the specimens themselves, have certain historical significance. Even without the missing box, which would have undoubtedly contained eight relatively common species that are still on the British list, there remain another 60 species in the collection, all apparently caught in the British Isles before 1920.

The Bree family has a long association with the church at Allesley, a village not far from Coventry in Warwickshire, and five family members were sequentially to be rector there over a period spanning 170 years, between 1747 and 1917. The last two of these incumbents, William Thomas Bree and William Bree, were father and son respectively and were to become noted amateur naturalists. It is worth giving a brief biographical account of them here, since their identities have been confused in the literature by a number of authors.

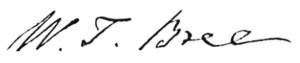

In his writings, the Rev. William Thomas Bree M.A. almost always referred to himself as W.T. Bree, most probably to differentiate himself from his own father, who was yet another Rev. William Bree (1754-1822).

W.T. Bree was born at Coleshill in Warwickshire and educated at the Grammar School in Warwick, before going on to study at Oriel College in Oxford. After being ordained in 1810 he was, for some years, curate in the village of Bickenhill, before succeeding his father as rector at Allesley in 1822, a post that he held for another 40 years.

From an early age, W.T. was a keen naturalist and he was to gain a considerable reputation as a local authority on botany, entomology, ornithology and, indeed, almost all aspects of natural history. For many years, he contributed numerous letters and articles to J.C. Loudon's Magazine of Natural History (published 1828-40) and The Gardener's Magazine (published 1826-1844), as well as a number of other scientific journals such as Edward Newman's The Phytologist (published 1841-54) and The Zoologist (published from 1843). His writings demonstrated the diversity of his interests and knowledge. W.T. showed a particular enthusiasm for phenology - the study of how animal and plant life cycles were affected by season and climate - and updated readers over the years with his observations on the first and last sightings of various birds and butterflies, in both Warwickshire and further afield. His reports showed that he must have kept detailed journals, recording species, places and dates over many years. The importance of W.T.'s detailed observations on so many aspects of natural history was recognised as recently as 1986 when a parasitic mite of butterflies, Trombidium breei Southcott (Acari, Trombidiidae), was named after him (Southcott, 1986). This was apparently in recognition of the careful records W.T. had made of the parasitisation of certain butterflies by red mites back in 1831 (W.T. Bree, 1832a).

From the writings of others, it is clear that W.T. corresponded with some of the leading naturalists of his day including, most notably, the botanist James Sowerby (1757-1822) and the naturalists Adrian Hardy Haworth (1767-1833), James Francis Stephens (1792-1852), Edward Newman (1801-1876) and John Obadiah Westwood (1805-1893). Of these, Haworth, who was responsible for writing Lepidoptera Britannica (1803-1828), the most authoritative work on British butterflies and moths to have been published at the time, appears to have been his closest friend. Haworth and W.T. corresponded regularly and W.T. evidently sent him unusual specimens of both butterfly (mentioned in Stephens, 1828) and plant. Haworth later wrote a botanical monograph on British species of Saxifraga and their allied genera, entitled Saxifragëarum enumeratio, in which he included the dedication:

To the Rev. William Thomas Bree, A.M., a successful cultivator and most accurate observer of Saxifragëan plants, the following dissertation on the natural order Saxifragëae is most respectfully inscribed, as a trifling testimony of gratitude and esteem, by his obliged friend, and humble servant, the author. (Haworth, 1821)

The Preface to the book gave an indication of how far W.T. travelled in pursuit of his interests in natural history:

This Essay would not so soon have appeared, had it not been for the solicitations, and through the assistance, of the author's valuable friend and coadjutor in collecting, cultivating, and communicating this Order of plants - the Rev. W. T. Bree, of Allesley near Coventry. For the furtherance of this purpose; he has personally examined many of the English, Welch [sic], and Scotch mountains, with unusual success: and those of Ireland, also, have yielded to his assiduity an abundant harvest of interesting matter. Nor has his zeal stopped even here; for it has induced him to purchase costly publications, without the aid of which the present Essay could hardly have been completed. (Haworth, 1821: xiii)

W.T. was credited in other contemporary botanical publications with the identification of localities for a large number of the rarer plants of Warwickshire (Purton, 1817-20; Watson, 1835).

(1).jpg) |  |

| The Rev. William Thomas Bree (1786-1863). From a Daguerreotype taken ca. 1850-60 |

In J.O. Westwood's magnificent book, British Butterflies and their Transformations (Humphreys and Westwood, 1841), there were numerous citations of W.T. Bree as a source of information regarding the habits and distribution of many species of butterfly.

Despite his position as rector at Allesley, W.T. found time for extensive periods of travel throughout much of the British Isles, to satisfy his love for 'botanising' as well as observing birds and insects. In terms of specific dates, we can read from his own publications that he visited the Isle of Wight in 1804-5, North Wales in 1809, the Lake District in 1810, Ireland (Killarney in County Kerry, Cork and Dublin) in 1814, Cornwall and the Scilly Isles for an extended period in the autumn/winter of 1817-18, Abergavenny in South Wales in 1824, Dover in August-October 1831, Oundle and the nearby Fenlands in July 1840, Dover again in September-December 1842, and Ilfracombe and Lynmouth in Devon in September-October 1846.

At the age of 69, W.T. went on a Grand Tour of the Swiss and French Alps. Through the auspices of his good friend, Edward Newman, he subsequently published some details of this trip in a booklet entitled Nugae Helvetica: scraps gathered during a tour in Switzerland in the summer of 1855 (W.T. Bree, 1856), which was reprinted a few years later in The Zoologist (1863). This was clearly an organised tour, in the company of others, and although W.T. noted the paucity of birds and mammals that he had seen on his excursions, he was obviously delighted by the many butterflies and other insects that he encountered. He noted:

Our tour, it should be observed, was not designed to be entomological. ... But the sight of so many butterflies that one had never seen before, or at least never seen before alive, and among them several which are justly considered to be of extreme rarity as natives of Britain, was enough to rouse the spirit of an old fly-catcher who had long since laid aside the net. I had provided myself with no sort of apparatus, either for capturing insects or preserving them when caught, save only a small corked box and some pins. The only implement I had of the former kind was my hat, and that hat a rather low-crowned, broadish-brimmed, flexible affair, which, I believe, would be called in the vernacular, a "wide-awake", perhaps the most awkward contrivance for the purpose that can be imagined. With this, however, I succeeded after a sort in taking some twenty species of Papilionidae, which I had never caught before, and now and then contrived to knock down an Apollo as he softly floated through the air ... (W.T. Bree, 1856: 5221-2)

W.T. remained fit and sprightly well into his later years and clearly retained his love of nature and travel. It was reported that he was well into his 70s when the sight of a rare plant tempted him into wading barefoot in a tarn on the Isle of Skye.

The scientific writings of W.T. Bree were known to Charles Darwin, who cited some of his observations in his own writings on natural selection. Darwin also described W.T. in a letter to the noted geologist, Sir Charles Lyell, in October 1860 as "old Revd Bree, a good miscellaneous observer of habits of all creatures - & botanist" (Darwin, 1879). What W.T. thought of Darwin's newly-published theories is not recorded, although his distant cousin, Dr Charles Robert Bree, wrote several highly critical reviews of them (C.R. Bree, 1860 and 1872).

W.T.'s son, William Bree, was born in Coleshill, Warwickshire, but spent his early childhood living at the Rectory in Allesley. For his education he was sent away to the grammar school in Bridgnorth, Shropshire, but each summer he spent some of his school holidays staying with the family of his uncle, the Rev. Richard Moore Boultbee. Between 1829 and 1848, Boultbee was rector of the parishes of Barnwell St Andrew and Barnwell All Saints, close to Oundle in Northamptonshire. This was to prove to be of great significance with respect to William's future interest in butterflies.

William went on to study at Merton College, Oxford (1841-44), from where he obtained an M.A. and later a D.D. 'by accumulation'. With his family background, it was inevitable that he would take Holy Orders. After his ordination in 1847, William's first appointment was as a curate in Polebrook, the neighbouring parish to his that of uncle at Barnwell St Andrew.

Although he was not as prolific a writer on scientific matters as his father, William did contribute a paper on the butterflies to be found in the immediate vicinity around Polebrook (W. Bree, 1852). He wrote that he knew of nowhere that could surpass the area for finding rare or less-common species of butterfly, listing 45 species that he had seen himself, plus two others reportedly observed by others. William spent 15 years in Polebrook, before returning to Warwickshire to succeed his late father as rector of Allesley in 1863. He was to remain there for the next 54 years, until his own death at the age of 94. During that time he was also to become Archdeacon of Coventry. Although married twice, he left no issue and his estate passed to his nephew.

(taken 1855-9).jpg) |  |

| The Rev. William Bree (1822-1917). Photograph taken ca. 1856 |

William Bree's nephew was Harvey William Mapleton. He was born at Badgworth in Somerset, where his father was the rector for some 50 years. He was educated at Malvern College in Worcestershire and then at St John's College, Oxford (1884-1888), before becoming a private schoolmaster for a number of years. In 1917 Harvey inherited the estate of his late uncle and, to satisfy a stipulation in the latter's will, he had to assume the surname of Mapleton-Bree by deed poll. He subsequently settled in Allesley.

Mapleton-Bree added to his uncle's butterfly collection through his own activities, and he was to replace many of the more common species with his own, presumably fresher, specimens. He continued to use his uncle's glazed book boxes to display the butterfly collection and did not resort to a cabinet. Even the extensive moth collection that Mapleton-Bree built up during his life was kept in standard wooden storage boxes. These moths were acquired along with the butterfly collection and most look to be a product of his own collecting, principally from sites in Somerset, Hampshire (where he worked) and Warwickshire. From the labels, his most prolific collecting period appears to have been between about 1913 and 1925.

Since Mapleton-Bree was never married, after his death in 1949 the family's butterfly and moth collections were sold at auction. What happened to them thereafter is not known, until they were found again almost 55 years later.

William Bree's interest in butterflies brought him into contact with the Rev. Francis Orpen Morris (1810-93), a keen naturalist and prolific author of natural history books. Morris was to visit William at Polebrook on 19-20 July 1852, for the purpose of collecting butterflies in the local area, and he mentions this in his finely-illustrated book, A History of British Butterflies, the first edition of which was published the following year (Morris, 1853).

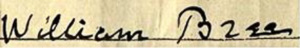

Morris was clearly impressed by the manner in which William stored his butterfly collection and, when discussing the design of suitable storage cabinets for Lepidoptera in his book, he stated:

All that I have said as to the desirableness and necessity of having a cabinet, and that a good one, for the preservation of your specimens, I still keep to; but I have since been made cognizant of another kind of receptacle for them, which is equally good in most respects, though not quite in all, and better in some. The Rev. William Bree of Polebrook, near Oundle, Northamptonshire, first shewed [sic] me this plan. It is to have cases made, such as backgammon or chess boards, resembling large folio books, corked and glazed inside, covered with leather, and lettered on the outside, at least they may be, "as you like it," "British Entomology," "Volume i," "Volume ii," and so on. (Morris, 1853: 14-15)

When rediscovered in 2004, the Bree butterfly collection was still housed in the very same boxes that Morris had seen and commented upon 160 years before. The hinged boxes are approximately 16" x 12" in dimension, and 3½" deep. They are constructed from a softwood carcass and covered with an embossed green paper, with labels applied as small leather patches. Inside they are lined with cork mats, covered in paper, and a tight-fitting glazed cover drops into the tray on each side of the box. Although the seal the glazed cover creates around the specimens is not as perfect as might be obtained in a cabinet drawer, it was presumably sufficient to offer some protection against pest insects. In terms of their practicality, it seems likely that these glazed boxes were intended to be a showcase for displaying insects, rather than a means of basic storage for a growing collection.

|

| Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

The boxes would have been obtained by William from a commercial supplier and were to become quite commonplace in the second half of the 19th century, so it is interesting that Morris had not come across them before he saw them in 1852. So who had made them? A likely candidate appears to be one Robert Downie (senior), a Scottish cabinet maker who had settled in Barnet in Hertfordshire. In the Census returns, he was recorded as an 'entomological cabinet maker' in 1851, as an 'entomological apparatus maker' in 1861, and as an 'entomological box maker' in 1871. During the 1850s and 60s he also developed and exhibited a new design of bee hive which, whilst still practical for obtaining honey, also allowed the beekeeper to observe the bees within the hive. His first mention in the literature in the capacity of a maker of the book-shaped insect boxes was in 1852, when Dr William Balfour Baikie wrote about his design:

Entomological Hints ... I wish to recommend to the younger lovers of this pursuit, placing specimens in boxes made in the form of books, with folding hinges, on both sides of which the insects may be pinned down. And here I cannot help mentioning the boxes of this description made by Mr Robert Downie, Union Street, Barnet, Herts, which are, for both neatness and cheapness, the best I have seen. His name is well known to all Entomologists of any standing, and I can only add my own less extended testimony to the efficacy and portable nature of his works. The sizes generally made are three, namely eleven inches by eight and a-half inches, thirteen by nine and a-half inches and sixteen by twelve; the prices being respectively five, seven and twelve shillings. (Baikie, 1852)

Soon after visiting William in Polebrook, F.O. Morris wrote to Downie and received more details of the apparatus he made. He was evidently so impressed with the man's catalogue, that he presented much of the information in the first edition of his own History of British Butterflies when it was published the following year - a significant endorsement. The largest book boxes made by Downie were described by Morris in more detail:

An improved book box, which excludes the air and dust from the insects, covered with green book cloth, gilt labels, corked top and bottom, sixteen inches by twelve; the same as those made by me [Downie] for the British Museum, and when shut up they resemble two volumes of a book: twelve shillings each. (Morris, 1853: 16)

|

| Part of the box containing some of the Lycaenidae Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

Before William opted for using these boxes, his father had evidently tried other means of storing his butterflies. In a letter published in The Magazine of Natural History, W.T. passed comment on a suggestion that had been made by James Rennie, professor of natural history and zoology at King's College, London, in his book Insect Miscellanies (Rennie, 1831):

Professor Rennie recommends the cedar, among other woods, for the purpose of constructing drawers for cabinets of insects. Let the inexperienced collector be warned that this is, perhaps, the very worst wood that can be employed for the purpose; a strong effluvia, or sometimes a resinous gum, exudes from the wood of the cedar, which is apt to settle in blotches on the wings of the specimens, especially of the more delicate Lepidoptera, and entirely changes the colour. I once had a whole collection of lepidopterous insects utterly spoiled from having been deposited in cedar drawers ... (W.T. Bree, 1832b: 364-369)

Sadly, of the earliest specimens in the collection, only a few have data labels indicating their provenance. If some of these were collected by W.T. Bree, this seems at odds with what is known about his character, since he was an assiduous keeper of records for almost everything he encountered in nature. It seems likely, therefore, that he must have recorded any information on his captures elsewhere, most probably in his journals. In his published writings he was often able to quote specific dates on which he had taken butterflies, sometimes even thirty years before. However, it is evident that he did label some of his butterflies, since the author has observed a specimen of Large Copper (pictured on the internet) that was labelled 'WTB', in what is recognisably W.T.'s own script.

Largely because of where they were caught, it would appear that a good number of the older specimens were collected by William Bree. They are also relatively easy to separate from the specimens collected by his nephew, Harvey William Mapleton-Bree, since they are on heavier pins and are often set in the 'old way', with the forewings not spread so far forward. In addition, Mapleton-Bree seems to have labelled his specimens with date and place of capture.

There are two specimens of the Bath White, Pontia daplidice (L.), in the collection; a male (now lacking its abdomen) and a female. An accompanying label, in the hand of William Bree, states that they were 'Taken by Mr. Le Plastrier of Dover'. This refers to Robert Le Plastrier (1776-1846), a watchmaker by trade who was well-known at the time as both a collector and purveyor of entomological specimens. John Curtis wrote of him: 'We recommend Entomologists who visit Dover to call upon Mr Leplastrier of Snargate Street, who disposes on very reasonable terms of British Insects principally collected by his son in the neighbourhood' (Curtis, 1827). Not long afterwards, when Curtis discovered a new species of moth near Dover, he named it Selania (Carpocapsa) leplastriana - the 'Dover Tortrix' - in honour of the watchmaker (Curtis, 1831).

The Bath White has always been a rare vagrant in the British Isles and, in the earliest days of butterfly collecting, instances of its capture are surprisingly well recorded in the literature. So how old are these particular specimens? It is known that W.T. Bree first visited Dover himself, for a holiday, in August-September 1831 and he naturally went to inspect the cabinet of Le Plastrier. In a letter to the Magazine of Natural History, written on 30 September 1831 whilst he was still resident in Dover, W.T. noted:

Mr Le Plastrier collects insects for sale and is, I believe, well known to many eminent entomologists. All collectors who visit Dover I would strongly recommend to apply to Mr Le Plastrier, whom, I will venture to say, they will find ready, in the most obliging manner, to communicate any information he may possess respecting the localities, habits, and periods of the insects to be met with in the neighbourhood. (W.T. Bree, 1832c: 330)

Bree went on to mention that he had observed:

A beautiful specimen of the male [Bath White], in the most perfect state of preservation, in Mr Le Plastrier's cabinet; taken in the meadow under Dover Castle, in the month of August. Mr Stephens also mentions having taken a specimen at the same place. (W.T. Bree, 1832c: 333)

|

| A male and female Bath White (dating to 1842) Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

A later record indicates that the male specimen had actually been collected by a son of Le Plastrier in 1825, but it was reportedly still in their possession in 1835. The other specimen, mentioned as having been caught by the noted entomologist James Francis Stephens, was taken some years before, on 14 August 1818 (Curtis, 1824a). There may have been another daplidice captured by Stephens at Dover, as early as 1815, as this appears to be mentioned in an entry in the diary of J.C. Dale on 25 July of that year (Colvin, 2013). Apparently, these were the only examples of this species known to have been collected in Dover until the summer of 1835, when at least three more were taken; two by Nathaniel Brown Engleheart and one, a damaged specimen, by a son of Le Plastrier (Engleheart, 1836). So, the Bree specimens appear to post-date this.

W.T. was to make a return visit to Dover in late 1842 - he mentions in one article trying to chase down a Small Tortoiseshell, still flying there on 15 December. He must have visited the watchmaker again as, in February 1843, he reported in The Zoologist that:

Mr Le Plastrier of Dover captured last summer, in that vicinity, two pairs of the rare Pieris (Pontia or Mancipium or whatever its right name is) daplidice, or Bath White. One of these fortunately laid some eggs after it was captured; and from these Mr Le Plastrier reared the caterpillars, which he fed with the wild mignonette (Reseda lutea), and at the present time he has four of them in the chrysalis state. (W.T. Bree, 1843a: 113)

He was to update the readers of the same journal at the end of May 1843:

In a former No. I stated that Mr Le Plastrier had in his possession last winter four specimens of Mancipium Dalplidice, in the chrysalis state, which he had reared from eggs laid by a female after it had been captured by him near Dover; and I then ventured an opinion that the flies would come forth in May. In this respect my expectations have been realised. In a letter from Mr Le Plastrier, bearing date May 18, 1843, he says - "I have the pleasure of fulfilling my promise, by informing you of the safe arrival of my four specimens of Mancipium Daplidice last week, and certainly they are of a splendid-looking insect, and of course, in fine condition; there are three females and one male". The above notice may not, perhaps, be wholly without interest to your entomological readers, as it serves to point out with precision the period when this rare insect makes its first appearance on the wing. I may add that Mr Le Plastrier states in his letter that he has the specimens to dispose of. I suspect he is the only English entomologist who has bred a native Daplidice. (W.T. Bree, 1843b: 201)

So, were the Bath Whites pictured here a pair of those specimens caught by Le Plastrier in 1842, or were they perhaps from the four butterflies that were successfully bred through by the watchmaker in 1843? Some 50 years later, when C.G. Barrett was discussing Le Plastrier's home-bred Bath Whites in his book The Lepidoptera of the British Islands, he mentioned that 'Mr Edwin Shepherd purchased four of these, which are now in Dr Mason's large collection' (Barrett, 1893). Shepherd was at one time Secretary of the Entomological Society in London (1855-66) and his collection did indeed subsequently become incorporated into that of Dr Philip Brookes Mason (1842-1903), a very knowledgeable amateur naturalist. Mason was to form one of the most complete collections of British Lepidoptera ever assembled privately, full of historic specimens (Chalmers-Hunt, 1976). Based on this information, all the evidence would seem to point to Bree's specimens being one of the two pairs 'taken by Le Plastrier' in 1842. They were presumably purchased by W.T. during his visit to Dover in that year.

The collection contains seven specimens of the Camberwell Beauty, Nymphalis antiopa (L.), another vagrant species in the British Isles. Five of these have labels indicating that they were acquired from entomological sales in the last quarter of the 19th century. The other two are much earlier, on heavier old-style pins. One of these has a label in the hand of William Bree, stating 'Purchased by W.T. Bree off Coulson, a watchmaker of Coventry, and said by him to have been taken near Warwick'.

Perhaps the most dilapidated specimen, and yet the most interesting, has a label in the hand of William Bree, stating:

Taken at Berkeswell, stuck with a thorn & placed in a case of stuffed birds, rescued and given to me by R.J. Mapleton, Curate of Berkeswell, Co. Warwick - W. Bree'.

|

| An early specimen of Camberwell Beauty Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

The Rev. Reginald John Mapleton (1817-92) was William's cousin and he was resident at Berkeswell from 1844-51, which presumably indicates the approximate age of the specimen shown here. The use of a thorn to impale specimens was not unusual amongst the earliest lepidopterists, but William evidently substituted it with a hefty pin. The original hole created by the thorn is still visible.

There are eight Swallowtail butterflies (Papilio machaon L.) in the collection. Some are unlabelled and could possibly have been collected by William Bree from around Whittlesea Mere, which lay just a few miles from where he lived for many years in Polebrook.

Perhaps the most interesting specimen is an unusual aberration (pictured here) in which the yellow patches on both the fore and hindwings have a diffuse (and not sharply-defined) end to them.

Two of the other specimens, which are labelled, were taken at Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire, in 1920, by the Rev. A.P. Wickham from Highbridge in Somerset. By their date, these must have been acquired by Mapleton-Bree, to add to the collection that he had inherited.

|

| An aberration of the Swallowtail butterfly Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

There are eight examples of the Large Copper, Lycaena dispar dispar (Haworth), in the collection. All are on heavy old pins and, although unlabelled, they were presumably caught in the fenlands of Cambridgeshire. Specimens of Large Copper collected by both W.T. and William exist in other collections. From the labels on those it is known that W.T. collected dispar at Ely Fen in 1832, and William collected it at Thorney Fen around 1846-7, both sites being in Cambridgeshire. However, like most locations in the fen country, these were in significant decline as breeding sites by the late 1840s, with changes in agricultural practices and the drainage of the levels seriously reducing the area in which these butterflies remained active. It is commonly held that the last specimens from Cambridgeshire were taken around 1851.

|

| Male and female Large Copper Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

It is known that, in early July 1840, W.T. had paid a brief visit to another well-known site for Large Coppers, the fens around Whittlesea Mere, but he was to be out of luck. Having travelled by coach from Oundle to Yaxley, he and a companion had hired a local guide who had evidently picked up some knowledge of local butterflies from past visitors. The guide claimed to have seen a 'great copper' on the wing a short time before and promised to take them to the same location. But the day 'proved nearly sunless, with wind, so that it was out of the question to expect to see many insects on the wing; and we were not so fortunate as to meet with a great copper' (W.T. Bree, 1851).

Although W.T. was writing about his recollections of this trip to Whittlesea some years after the event, his reasons for doing so appear to have been out of an awareness of the ecological disaster that was about to occur there. He wrote:

The object of the present communication is to record (so far as memory serves me) some of the rarer plants which we met with in the morning's excursion. And I do this because Whittlesea Mere itself, together with its surrounding fens, is doomed at no very distant period, to be converted into useful, homely, arable and pasture land; when of course its botanical and entomological treasures must be for the most part, if not entirely, annihilated. ... The splendid Lycaena dispar, while once captured here so abundantly, is now, I am told, scarcely, if at all, to be found in this locality. Its existence in Britain will probably ere long be mere matter of history. (W.T. Bree, 1851: 100-101)

The possible existence of populations of the Scarce Copper, Lycaena virgaureae (L.), in various locations throughout England has long been debated. In a thorough review given in Emmet and Heath (1989), it was pointed out that although many of the earlier writers included the 'Scarce Copper' or 'Middle Copper' in their books, none claimed to have seen one alive themselves. By the latter half of the 19th century, many authors chose to exclude it as a confirmed British species, possibly preferring to believe that any specimens in circulation had been deliberately imported by dealers trying to fool early collectors. Others have argued that the numbers of reported captures and sightings from the 18th and 19th centuries are sufficient to suggest that there might have been a number of small local populations that were slowly reaching extinction at about the time that people's awareness of unusual species of butterfly was on the increase. Curtis (1824b) claimed that virgaureae had once occurred in the fens of Cambridgeshire, but concluded that it seemed to have become an extinct species in Britain. Despite that, 'specimens were in all the old Cabinets'.

There are two specimens of Scarce Copper in the Bree collection (pictured below), a stunning male and a worn female. Both are fixed with very heavy old pins, but there are no labels indicating where they were taken.

|

| Male and female Scarce Copper Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

The only clue to the provenance of these particular specimens comes from Barrett (1893). In his volume on British butterflies, he makes regular reference to information provided to him by Mr Charles Adolphus Briggs (1849-1917), a solicitor and keen amateur entomologist who became a major collector of British Lepidoptera in the latter quarter of the 19th century. Barrett stated:

Mr C.A. Briggs has a specimen [of Scarce Copper], in poor condition, which was taken by his uncle, and which he knows to be native. He also informs me that a female specimen was captured in this country by Archdeacon [William] Bree, and is still in his cabinet. (Barrett, 1893: Vol. 1, 56)

C.A. Briggs just happened to be a first cousin (once removed) to William Bree and knew him well. They would have corresponded over entomological matters and Briggs may well have visited Allesley and seen the collection. If the Venerable Archdeacon William Bree claimed to have captured a specimen himself, it is this author's opinion that he has to be believed. However, it is a pity that he did not record where it was taken. It seems probable that the 'uncle' of C.A. Briggs referred to by Barrett was in fact W.T. Bree, his great-uncle. If so, this could indicate that the worn female specimen pictured here was taken by W.T., whilst the brighter male specimen was captured by William, most probably somewhere in the Fens during the time that he was living in Polebrook.

Barrett (1893) went on to suggest that the capture of these Scarce Coppers and a few other casual specimens, with so little additional information regarding them, did not indicate that the species had been an inhabitant of this country in recent times. Instead, he believed that they may have been accidentally introduced in the larval or pupal state with plant material brought from abroad. We shall perhaps never know for certain. Ironically, when discussing this particular species in his book, The Aurelian Legacy, Salmon (2000) makes the throwaway comment that 'Bree favoured the inclusion of Continental specimens in British collections to make these complete'. There is no reference in the text indicating on what basis this statement was made. Having now had the benefit of being able to inspect the Bree collection itself, there is no evidence of foreign specimens being included within it and so Salmon's comment seems unfounded.

There are five specimens (three male and two female) of the distinctive Mazarine Blue, Cyaniris semiargus (Rottemburg). Only one is labelled, in the hand of William Bree, and simply states 'Glamorgan'. Elsewhere, W.T. recorded that he had captured this species himself in an open plantation close to Coleshill Park in Warwickshire, in June 1804, and from a woody situation at Hinkley in Leicestershire, in July 1812. As a consequence of this, he was perhaps the first person to observe that that it was not 'peculiar to chalk districts, but seems to delight in woody situations abounding in grass' (W.T. Bree, 1833).

|

| Three male and two female Mazarine Blues Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

The Chequered Skipper, Carterocephalus palaemon (Pallas), which is now confined to a small area in the west of Scotland, was once considered to be locally common in various areas of England, including Northamptonshire. William (who knew it by the name Hesperia paniscus Fabr.) stated it to be 'not uncommon' at sites close to Polebrook (W. Bree, 1852). When F.O. Morris published his History of British Butterflies in 1853, he indicated that his plate for this species (which he called the 'Spotted Skipper') had been drawn 'from specimens in the cabinet of the Rev. William Bree'. There appear to be seven of William's specimens still present in the collection, and six other labelled specimens added later by Mapleton-Bree, from sites in Northants and Lincolnshire.

There are also nine specimens of the equally-localised species of Silver-spotted Skipper, Hesperia comma (L.). These were almost certainly taken by William, who stated that they were 'rare' during his time at Polebrook, only being found in a rough field adjoining Bull-nose Coppice, close to Barnwell Wold, in the month of August (W. Bree, 1852). Barrett was to give more details of the relatively brief existence of the species at this site:

In Northamptonshire there is a singular record. The Rev. W. Bree states that it appeared suddenly at Barnwell and Ashton Wolds in 1851, in a district which is not upon chalk, and in which it had not previously been known to occur. It seemed as though a flight of this species suddenly arrived. Here it continued to be found until the wet season of 1860, when (with Polyommatus arion, as already stated) it totally disappeared from the district, and there is no subsequent record there. (Barrett, 1893: Vol. 1, 297-298)

|  |

| The Chequered Skipper Image © Mike Mead-Briggs | The Silver-spotted Skipper Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

There are twelve specimens of the Black Hairstreak, Satyrium pruni (L.) on old pins. With respect to this species, Morris (1853) stated that at 'Barnwell and Ashton Wold, and the neighbourhood of Polebrook ... the Rev. William Bree has captured it in plenty'. In fact, that neighbourhood once boasted all five British species of hairstreak (W. Bree, 1852).

|

| The Black Hairstreak Image © Mike Mead-Briggs |

The book-box that is missing from the collection would undoubtedly have contained, amongst other species, examples of the Purple Emperor, Apatura iris (L.), that William regularly saw and collected from the woodland rides around Barnwell Wold and Ashton Wold, close to his home in Polebrook.

Following the previously-mentioned visit of F.O. Morris to stay with William in July 1852, he was to record in his book, A history of British butterflies:

Thanks to the obliging hospitality of the Rev. William Bree, the curate of Polebrook, to whom I had no introduction but that which the freemasonry of entomology supplies to its worthy brotherhood, I had the happiness of beholding His Majesty, or so to speak more correctly, Their Majesties, though, as is only proper, at a most respectful distance; they at the "top of the tree," and I on the humble ground. The next day, in the same wood, at Barnwell Wold near Oundle, Northamptonshire, during my absence in search of the Large Blue ... Mr Bree most cleverly captured one ... That specimen, a male, as a practical illustration of the lesson, now graces my cabinet, together with the first female that its captor had ever taken, both obligingly presented by him to me. Since then, I have just heard from him that he took another the day after I left him, in one of the ridings in the wood, in his hat. (Morris, 1853: 85-86)

Morris added that his plate of the Purple Emperor was drawn from the specimens given to him by William Bree on that occasion. In later editions of the book he added the note, 'Since then, in 1854, Mr Bree captured nine in one day in three hours, three of which he has given to me'. William himself was to describe one particular aberration of Apatura iris that he had caught at Ashton Wold, in which the main white band across the wings, and some of the white spots that are normally present, were lacking (W. Bree, 1858).

Some of William's specimens of Apatura iris are to be found in the Hope Collection in Oxford, being donated in 1860 (Smith, 1986).

At the centre of the storage box containing the fritillaries, is a singularly large specimen, the history of which was first described by W.T. in the Magazine of Natural History, back in 1840. The butterfly had originally been caught in 1833 by a friend of his son, to whom it was subsequently given. When William showed it to his father, W.T. identified it as an American species, the Venus Fritillary Argynnis aphrodite (Fabr.). In his article describing this newly-discovered species for the British Isles, W.T. explained why he believed it to be an adventive specimen (an accidental introduction), rather than a case of some deception carried out by an unscrupulous dealer through whose hands he argued it could not possibly have passed (W.T. Bree, 1840). J.O. Westwood, whose book British butterflies and their transformations came out the following year, agreed with this conclusion, but still chose to include an illustration of the species (Humphreys and Westwood, 1841), as did F.O. Morris many years later, shortly after he had seen the very same specimen first hand in the book-boxes belonging to William Bree (Morris, 1853).

Having been rediscovered in the collection in 2004, a closer inspection of the actual specimen has indicated that the butterfly had been misidentified all along, and that it is in fact the very similar-looking species Argynnis cybele (Fabr.), commonly known as the Great Spangled Fritillary. This American butterfly had itself never been recorded in the British Isles and so a paper was duly published correcting this 170-year-old error (Mead-Briggs and Eeles, 2010).

I would like to thank Steve Lane, formerly Keeper of Natural History at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum in Coventry, who some years ago went to the trouble of digging through old emails in order that he could put me into contact with the finder of this lost collection. My 5x great uncle, the Rev. William Thomas Bree, would have appreciated that act of kindness.