|

by Philip E. Howse.

This book develops and extends the author's views about the evolution and defensive aspects of mimicry in butterflies and moths set out in Seeing Butterflies; focusing on some of the most incredible insect mimicry that exists in tropical forests throughout the world.

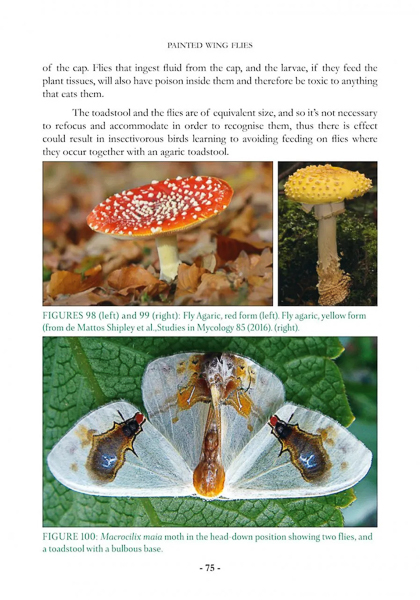

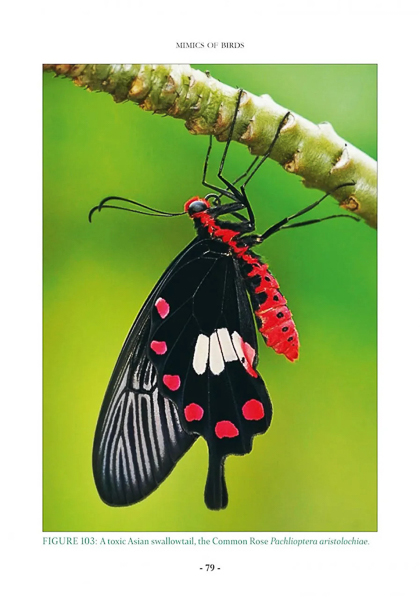

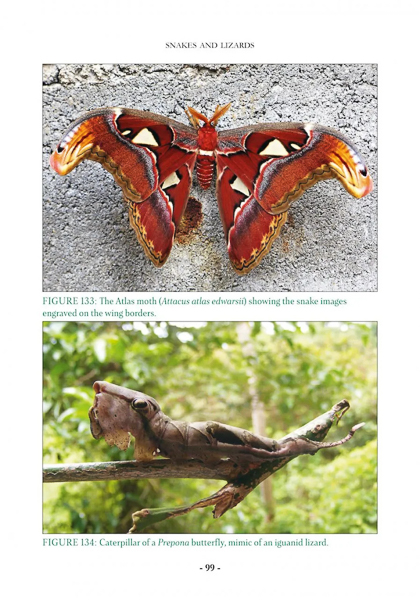

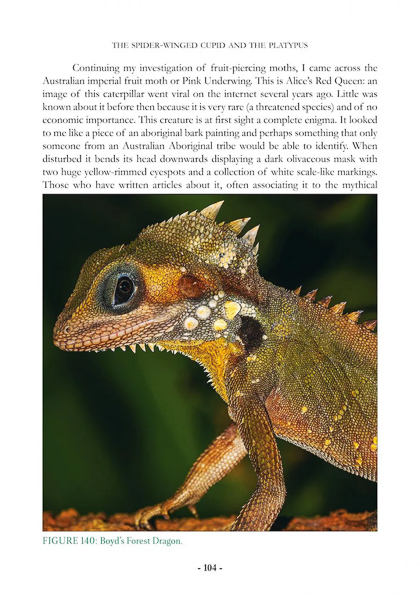

It reveals what no museum collection can tell us about the evolution of mimicry that has produced creatures that can be mistaken by predators for dead leaves, toxic beetles, scorpions, venomous snakes, lizards, frogs, bats, or insect-eating birds. A selection from hundreds of thousands of photographic images shows how butterflies and moths in their natural environment deceive their enemies with their colour patterns and behaviour.

The book introduces us to an amazing world that most naturalists and biologists never knew existed, and explains why this is so. For biologists, this book opens up a new dimension to our understanding of evolutionary theory. For others it will, it is hoped, intensify their desire to help preserve the precious environments in which these seemingly alien but astonishingly beautiful insects are to be found.

This book is a continuation on the theme extolled by the author in several previous books on Lepidoptera, e.g. Messages from Psyche (2010), Seeing Butterflies (2014) and The Bee Tiger (2021), and expands the view that when we look at butterfly and moth wing and body patterns and behaviour in relation to mimicry, be that cryptic, Müllerian or Batesian mimicry, we often make the mistake of seeing these creatures through human eyes, rather than in the way that a potential predator - arthropod or vertebrate - might see them. By this means, as the author readily and comprehensively explains, we are surely in error. As he further argues, these prey items have been in a war, an 'arms race', with such potential predators, perhaps over tens of millions of years (although the time period could be much shorter of course; see below) and as such, it is beholding on the prey to adapt and, by so doing, survive (he evokes mention of the Red Queen hypothesis ... the prey running to stand still as the predator chases it through ecological-evolutionary time and space ... metaphorically speaking). It is not so much 'survival of the fittest' by a process of 'adapt or perish' governed by intense natural selection, but more 'survival of the survivors'. And to do this the prey have to produce tricks of imitation and behaviour worthy of the finest magicians: 'Now you see me, now you don't', as the insect in question merges to become a leaf, twig or flower, or it displays flash warning colouration, enough to startle the predator and give the prey time to escape to survive another day.

|  |

|  |

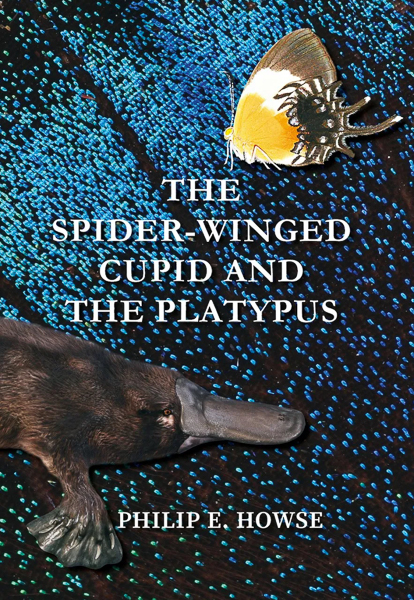

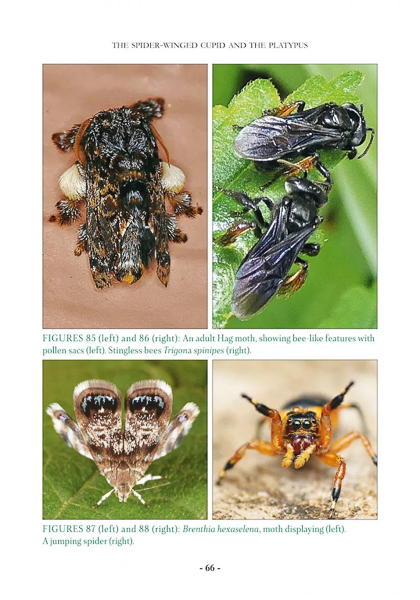

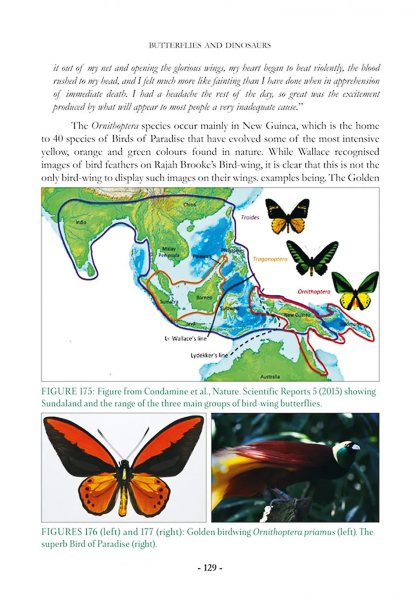

Unlike his previous works, he develops the central theme of Lepidoptera mimicry in relation to other animals besides birds including mammals, e.g. bats, tigers and humans. It is surely a tour de force, a work of considerable scholarship, and as such, a revelation to all those interested in nature, evolution, and ecology, the last the cutting edge of evolutionary processes. The text, which is always interesting and holding of one’s attention along with the plethora of magnificent colour photos, generally carefully chosen to exemplify the themes and arguments expounded, are fantastic. Whether the reader believes all the associational examples provided by the author, e g. blue butterfly pupae imitating human faces, certain Nymphalid butterflies showing tiger head coloration, including stripes, and moths pretending to be bats hanging upside down in order to 'fox' (if that is the word) their enemies, real bats, is another matter. I was largely - but now wholly - convinced by some of the more extreme and tentative associations. The photo of the fruit fly that has evolved shapes on its wings mimicking ants is amazing beyond belief and anyone, even the most eminent evolutionist, who claims that he or she understands how such a designs can ever develop, then let them step forward. Having said that, unlike us humans and our still limited gifts in the field of molecular biology, nature has endless time, endless opportunities to evoke change and endless resources. Hence, it can produce animals like the stegosaurus, the platypus and the spider-winged cupid butterfly, a butterfly with a clear spider pattern on the ends of its hind wings. By the way, the platypus is only mentioned to show the reader that long ago, some two hundred years to be exact, when these animal were first observed and captured in Australia, the cognoscenti of the day assumed (wrongly) that the animal was a hoax. Prof. Howse by extension, understands that some of the mimicry he describes is so 'out of this world' that it is difficult even for present-day biologists and natural historians to really believe what they are witnessing.

|  |

|  |

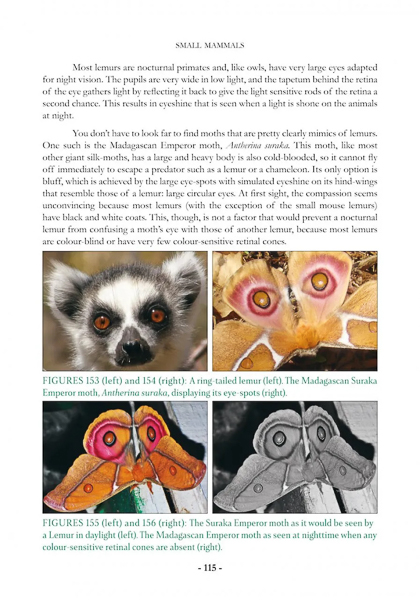

The author also informs us about human psyche and how we are geared up mentally to see images in the world around us that appear to be human faces or animals, and if we do this, why not predators such as birds too? A fraction of a second of doubt on the part of a predator is valuable escape time for the threatened prey. What the book and its thesis does surely emphasise is that the visual acuity of birds especially in detecting suitable prey is incredible. It is because of this acuity that the selection pressure on the prey is so great, and thereby it positively drives the evolution of these bizarre defence wing and body patterns and strategies, sometimes to the most outrageous forms. This includes adult moths appearing like hornets, and lepidopterous larvae evolving to look like tree snakes and even predatory beetles. Maybe, because of this intense selective pressure, the time span of evolutionary change is much shorter than we imagine. We tend to think that evolution only occurs over vast swathes of time, periods we humans cannot imagine anyway. But in reality, due to the rapid rate of reproduction of some insect species relative to their predators such as birds and reptiles, it may be faster than we think.

|  |

|  |

So far, all very positive. But, alas, there are some serious negative issues with this volume too. The most egregious are the many textural errors, the worse being the incorrect labelling of some photos in relation to the text, the wrong accreditations of the photos themselves and the misspelling of the Latin names of some the creatures mentioned. As bad as these things are, nevertheless, the storyline somehow survives this trauma and all these various errors can surely be changed quickly in a revised edition, which is what I strongly urge the author to do

|  |

|  |

In conclusion, I suggest that every biologist should buy and study this book for themselves and then say that they are not stunned by what they see and read therein.

|  |

To order this book, please visit Butterfly and Amazonia Books.