|

by Philip E. Howse.

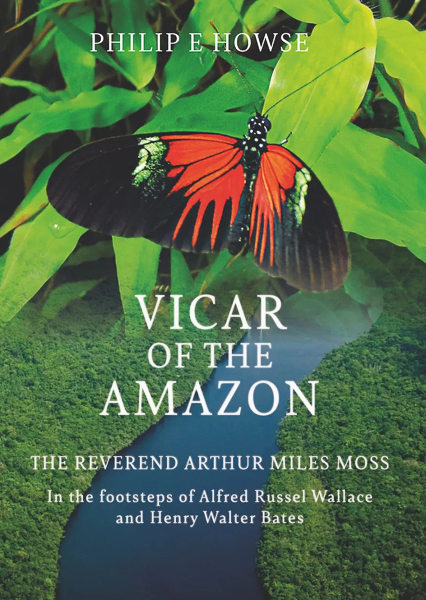

Prof Philip Howse's book Vicar of the Amazon, chronicles the life of the Reverend Arthur Miles Moss, a little-known genius who explored the Amazon, collecting and breeding butterflies and moths in period from 1903 to 1947 - a period during which little about the Amazon and its natural history became known to the world.

Miles Moss went to Peru in 1907 and from 1912 to 1945 was the Anglican Chaplain of the largest parish in the world, one that encompassed the whole of the Amazon basin from Iquitos in Peru to the Atlantic; an area roughly 3,000 miles long and 800 miles wide, amounting to about one quarter of the South American continent. His great passion was Lepidoptera: his major contributions to science were in the form of three classic works on hawk-moths and swallowtail butterflies, all published in the journal of his patron Lord Walter Rothschild who established Tring Museum containing the largest collection of butterflies and moths in the world.

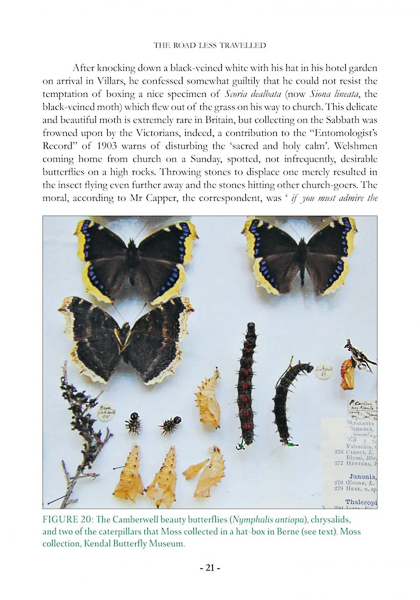

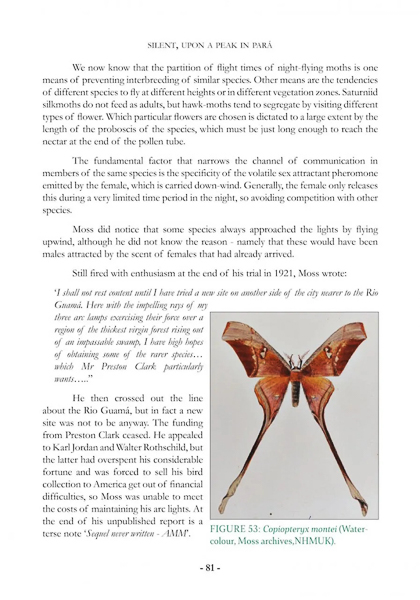

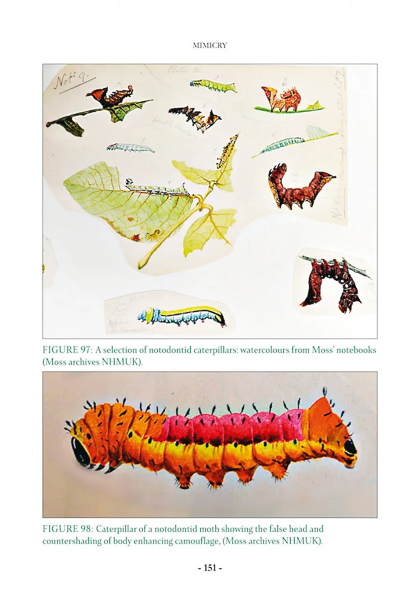

Following in the wake of great Victorian naturalists such as Wallace and Bates, Moss' story has been neglected: apart from his publications in scientific journals he left a collection of 25,000 insects, unpublished manuscripts on Amazonian natural history, and some incredibly beautiful water-colours of bizarre-looking caterpillars now archived in the Natural History Museum in South Kensington.

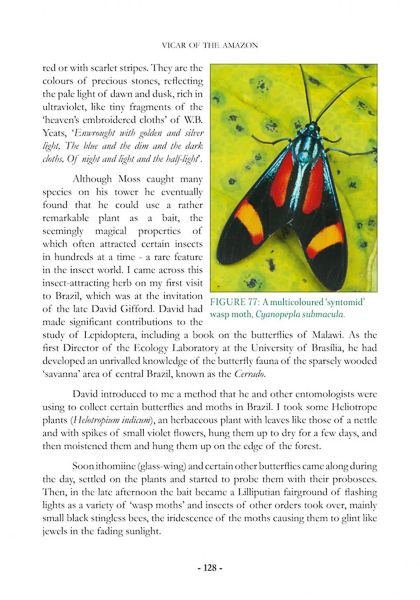

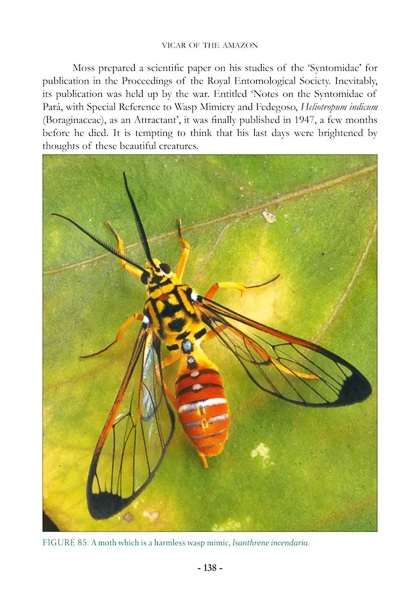

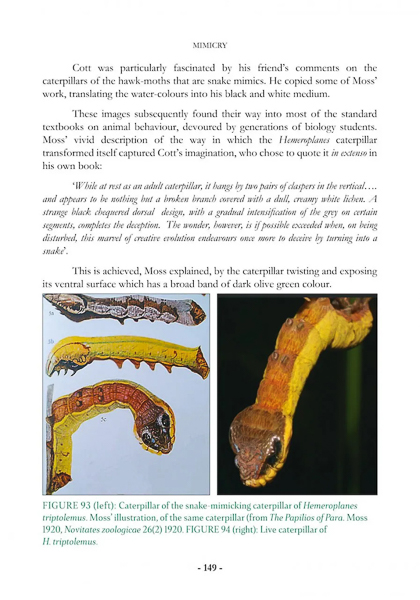

A new biography of an early naturalist in South America! Among my favourite subjects; I couldn't wait to read it. And I was not to be disappointed by this account of the life and times of Arthur Miles Moss (1872-1948), a highly significant but almost forgotten figure: clergyman, musician, artist (in paint), naturalist and, perhaps most importantly, lepidopterist. In anticipation and to get my geographical bearings I skimmed a few sections of my ancient copy of Wallace's Travels on the Amazon, and re-read notes made on my own limited journeys in the region (not as a lepidopterist, though you can't ignore the gaudy spectacle of those butterflies and moths). That preparation was soon forgotten as I became absorbed in the life and times of the Reverend Moss, in a book richly and relevantly illustrated with superb photographs, mostly in colour, including many of Moss's own perfect paintings of insects, as well as some of his landscapes and waterscapes.

|  |

|  |

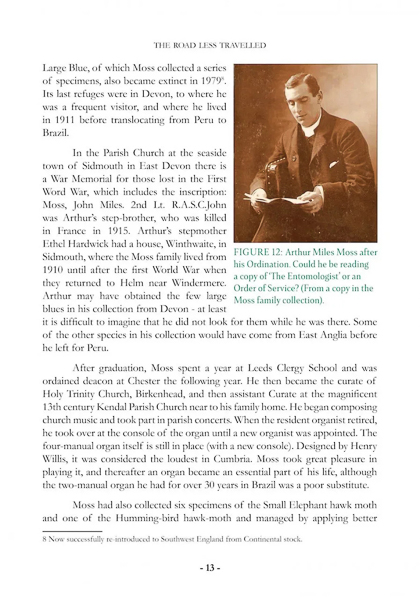

We first learn about Moss's early life in the Lake District, around Morecambe Bay, and at Cambridge, about his developing talents as a musician (singer, organist and composer) and painter, and the beginnings of his obsession with moths and butterflies. Perhaps inevitably, he was ordained in the Anglican Church, which provided the opportunities for travel and for pursuing his hobbies, especially entomology.

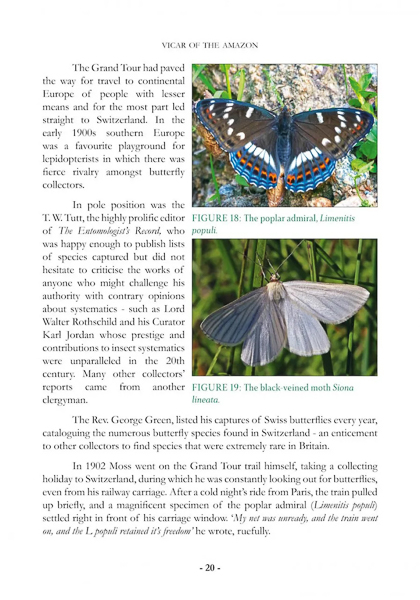

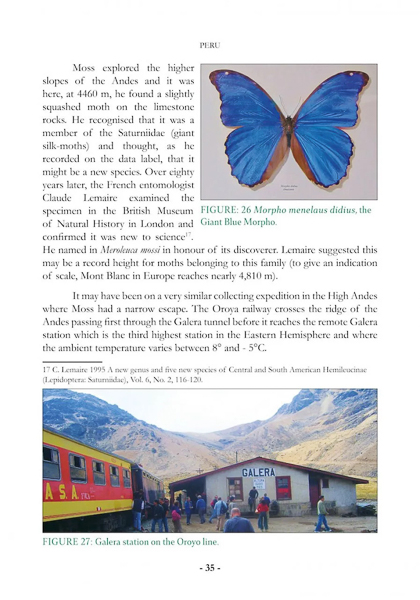

After various church positions in England, including a break in Switzerland (an important place for lepidopterists, it seems), he did not hesitate to take up an appointment at the Anglican mission in Lima, Peru. The chapter on his three years there provides (for me anyway) unexpected insights into the contemporary history of that country, notably on its industrial development and associated troubles.

|  |

|  |

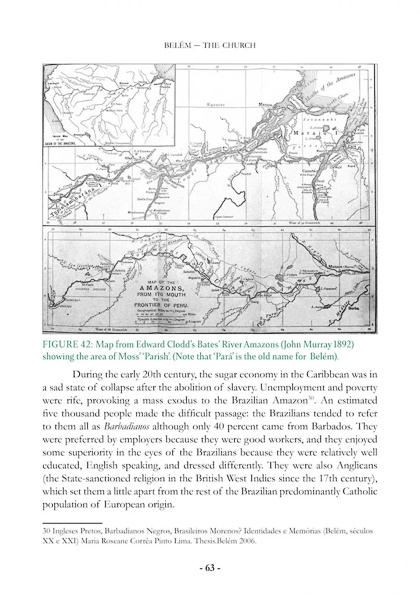

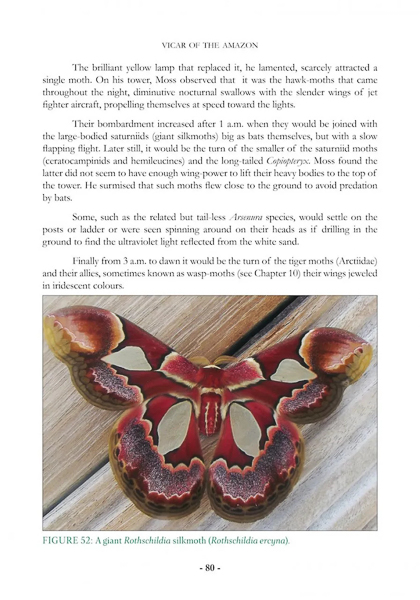

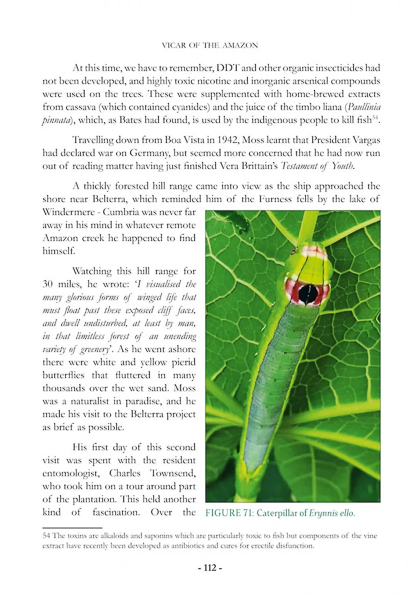

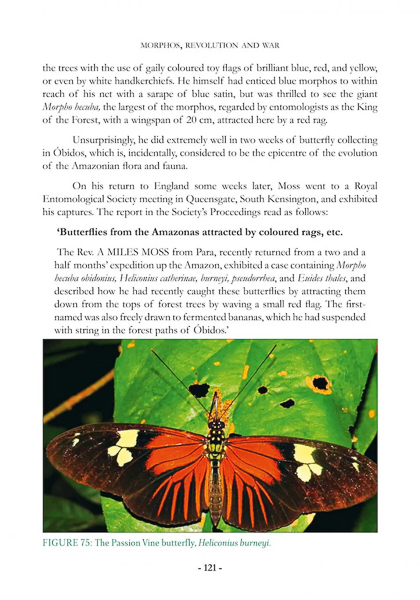

The next ten chapters cover the thirty-three years that Moss was based in Belém at the mouth of the Amazon, following his appointment as honorary Anglican chaplain, vicar of "the largest parish in the world". These chapters follow an approximate chronological sequence. Some focus on significant events such as setting up the vast, ill-fated Fordlandia rubber plantations (and the ecological issues that contributed in part to its failure), the attempted Paulista revolution, and the peripheral involvement of the region in World War II. Others concentrate on Moss's major interests, such as particular moth or butterfly groups, his concern to understand complete life cycles of individual species, and the extensive occurrence of mimicry. The enjoyable chapter on mimicry (the author's recent speciality) is especially rich in reproductions of Moss's own brilliant insect paintings. The last of the Belém chapters considers, among other things, the difficult issue of how Moss attempted to reconcile his religious beliefs with Darwinism; dealt with most satisfactorily, I thought. The concluding chapter deals with Moss's eventual post-war return to England in old age and ill health, unhappy and missing his parish in Brazil, and the eventual disposal of his collections, from Tring (Rothschild's collection) to the Natural History Museum.

|  |

|  |

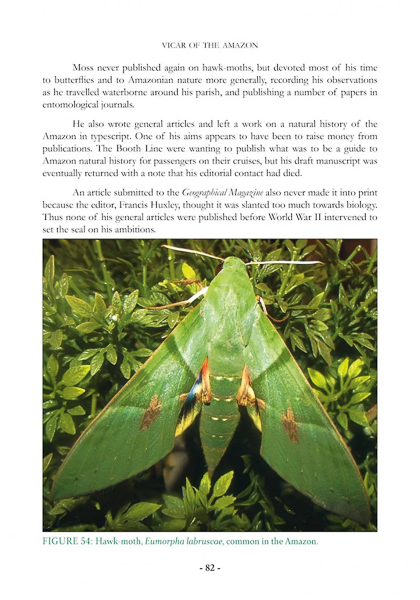

Whilst the lepidopteran science is presented in an entertaining and easily understood way, I particularly enjoyed the descriptions of Moss's travels through his immense and watery parish, with emphasis on his searches for rare and exotic moths and butterflies, sometimes developing innovative methods for trapping and study. We learn also of the contacts or collaborations he necessarily made with many contemporary collectors and scientists, notably with Margaret Fountaine during her extended visit to Belém and the Amazon.

Though large and quite heavy (but very moderately priced), this book was a pleasure to read, especially with such superb illustrations throughout. The numerous typing or printing errors that have slipped through the proof-reading net are invariably trivial and so, like the often clumsy sentences, are not a serious distraction (though I am not persuaded that the Andes are in the Eastern Hemisphere, p.35).

|  |

|  |

Professor Howse is to be congratulated on his rediscovery of Moss and for bringing to light his achievements in this attractive biography. Whether you are interested in tropical butterflies and moths, general natural history, travel and adventure, or the present-day plight of the Amazon basin (and the consequences for us all of its continued mismanagement!), I am sure you will enjoy reading Vicar of the Amazon.

|  |

To order this book, please visit Butterfly and Amazonia Books.